-or-

A Tale of Two Coats * with side-quests!

by

THL Rannveig Hrajshvelgsneys Alfvinsdottir of the Barony of Blackstone Mountain

Born out of a desire for fancy garb that didn’t need a belt, this documentation is primarily a compare and contrast of the commonly called Turkish-Venetian coats seen in Italian Renaissance art throughout the late 1500’s, and the equivalent coats of the Turkish Ottoman empire.

Additional brief forays into the synergy of Italian painters, the complex relationships of frenemies, and a Spanish tailors manual, are also included.

Introduction:

How this project started.

For a while now, my “guilty pleasure garb,” for when I just want to look fancy with minimal effort, has been some sort of vaguely Turkish coat worn over…whatever…and often accessorized with too much jewelry.

Earlier this year, after seeing me toss on a Turkish coat over my Renaissance underwear, my good friend THL Verena von Talhain showed me an Italian painting of a lovely woman wearing a luminous silk coat paired with a simple chemise and lots of pearls.

Here was the aesthetic I had been searching for!

Alessandro Varotari (Italian, 1588-1649)

Although convinced it was most likely allegorical, I decided I had to make this outfit! However, once I started researching, I discovered more and more paintings with similar coats from the same period by different artists!

Perhaps this was not an allegorical garment and was a commonly worn style after all!

However, I also started to notice that all the paintings looked similar.

Like really really similar.

With identical folds in the fabric and identical braids in the hair across multiple paintings by multiple artists.

So, was this a common garment that was popular in Venice throughout the 1500’s, or had I found the 16th century version of Glamour Shots?

I decided to track down as much information as I could find regarding these paintings to try and better understand the context, AND ALSO still make myself a fancy silk coat.

And that dear friends (after three coats, and plus a few side-quests) is how we got here.

The Paintings

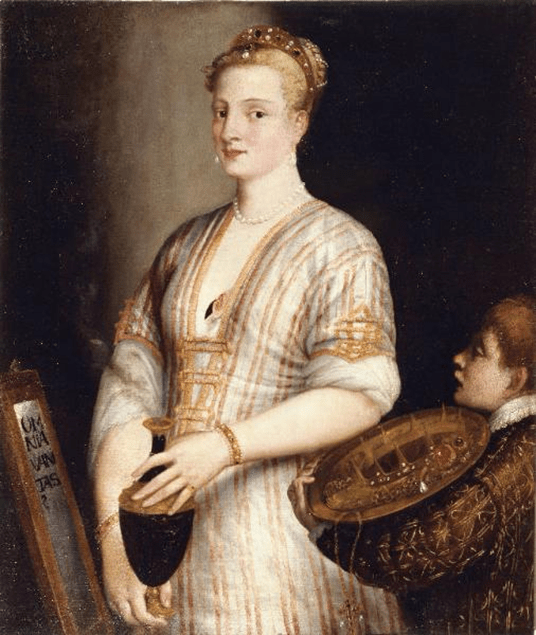

Titian, c. 1550

Titian, c. 1550

Alessandro Varotari, c.1620

This one has one of my favorite sleeve embellishments!

Titian, c.1485-1576

Portrait of a Lady as Saint Mary Magdalene

Alessandro Varotari, c.1588-1648

*Note from Rannveig: The above image is from an art auction site, and I don’t believe they have it attributed correctly. I believe this was a copy by a different artist of the painting below.

Alessandro Varotari, c. 1588-1648

*Thank you for including that clearly defined shoulder seam Mr. Varotari!

Sacchis Giovanni Antonio, c.1483-1539

# fashion goals

# my aesthetic is to be an allegory of vanity

Titian, c.1550–60

The above image, while not the exact same sort of coat, particularly with the sleeves, shares many similarities with the others. I believe this is depicting a garment that I have heard called a zimarra, and that i am looking forward to looking into more!

Portrait of a noble lady, three-quarter-length, in a red dress

Provenance:

Art market, Vienna, 1970s

workshop of Titian, ca. 1515-20

I love the above painting for several reasons.

The hybrid of the Venetian style coat with the “exotic” Turkish headdress. The striped texture of the coat’s fabric.

Of note: the many details that match the painting above it, including the trim, ferret, opened buttons, and bracelets.

Antonio Vassilacchi.

In reference to the above image: “The coat was likely worn as seen above inside the home as a type of dressing gown.

It could have been worn alone outside the home as depicted in this find of a Turkish Venetian crossover dress painting from the late 16thCentury that has two ladies in public with this dress on. I found this at the Doge’s Palace Museum in Venice! It is the “Coronation of Baldwin of Flanders as Latin Emperor of Constantinople” by Antonio Vassilacchi. Very happy about noticing the main one in blue and then another possible one on the upper balcony in a reddish brown.”

Quote is from la Bella Donna Historical, who found and shared this delightful image on her blog about Turkish Venetian coats!

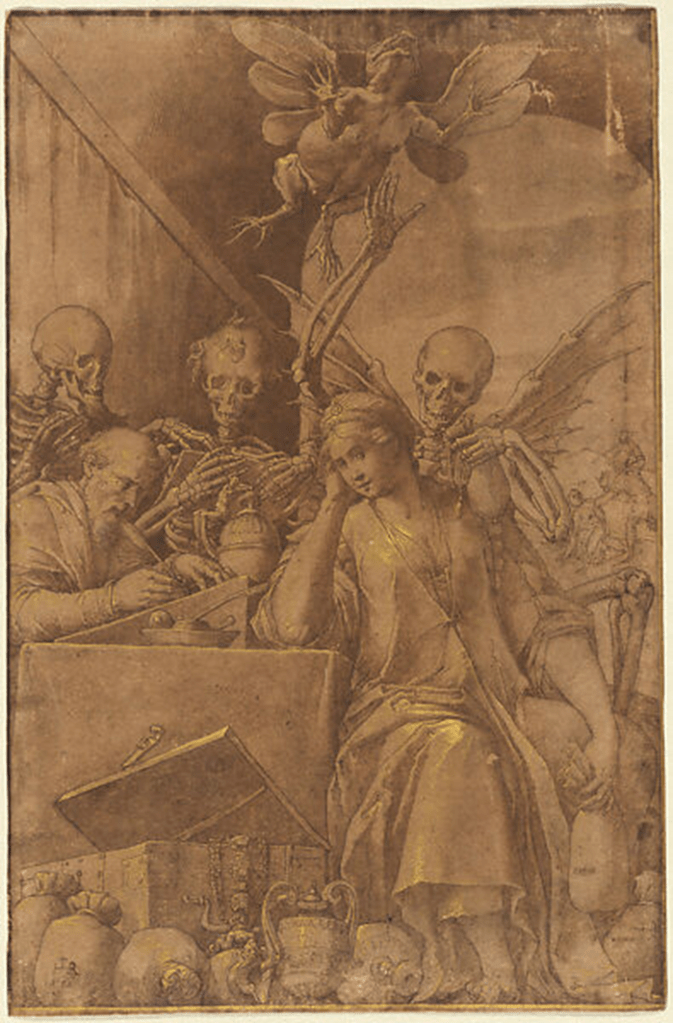

Palma Giovane, unknown date.

“In 1590 Ligozzi created a series of elaborate, allegorical drawings of the Seven Deadly Sins (six still exist). This painting, which is a fragment, depicts the central figures of the allegory of Avarice, the drawing for which is in the National Gallery, Washington. As described in emblem books, Avarice is shown as a pale woman holding a bag of money. The threatening skeleton suggests that the artist was inspired as well by other representations of the vice in either literature (perhaps Dante) or the visual arts.”

Description from: The Met Museum.com

https://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/436888?utm_source=Pinterest&utm_medium=pin&utm_campaign=wickedworks

Also Known As:

An accurate depiction of me trying to get this documentation done while faced with the distractions of other projects, my cat, and a new video game.

*Mostly I just love this drawing and the way the sheen of the silk is captured, so I thought I would share it too.

The Painters

Titian

The Workshop of Titan

Follower of Titan

Alessandro Varotari

Sacchis Giovanni Antonio

Antonio Vassilacchi

Palma Giovane

Jacopol Ligozzi

That’s a whole lot of artists painting nearly identical images.

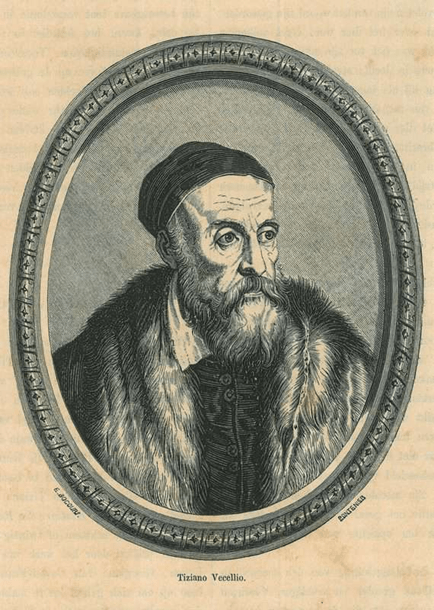

And it all begins with Titan, who, born sometime around 1488-1490 in the Republic of Venice, would become one of the great masters of Italian Renaissance painting.

“Titian and his paintings”

https://www.titian.org/

Titian’s Legacy:

Imitation as flattery, and artists gotta pay bills too.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) left an indelible mark on the artists who followed him. His mastery of color and dramatic composition became a benchmark for painters, his period contemporaries, and the generations to follow.

Many of these artists actively studied and emulated Titian’s work, often copying his compositions or reinterpreting his themes.

Alessandro Varotari, for instance, made deliberate stylistic shifts mid-career to align with Titian’s use of colors.

Meanwhile Antonio Vassilacchi and Jacopol Ligozzi both adopted his dramatic lighting and rich palette to elevate religious and mythological scenes.

Additionally, around the same period that Titan was becoming a towering figure of Venetian Renaissance painting, there was a distinct genre of portraiture gaining popularity in Italy celebrating the “Bella Donna”, or the Beautiful Woman, as an emblem of idealized femininity, sensuality, and virtue.

These paintings, often anonymous or loosely based on mythological figures, were not actual portraits so much as artistic portrayals of beauty. Artists such as Titian painted women with luminous skin, flowing or fantastically adorned hair, and luxurious garments, embodying the Renaissance ideals of grace and charm.

The repetition of similar poses and features across paintings reflect both artistic admiration and market demand, as these images adorned private homes and served as symbols of status and taste.

I believe that the abundance of similar paintings by so many different artists stems from a combination of reverence, popular appeal, and workshop practices.

Titian’s compositions were widely admired and commercially successful, prompting artists to reproduce or adapt them for customers eager to own a piece of popular art. In many cases, repetition was not mere imitation, it was a homage and a way to participate in the rich (and profitable!) art style Titian had defined.

The Coats

Sooo…. are these just imported Turkish coats worn by Venetian women?

This question led me to a focused dive into what differentiates a Turkish/Ottoman coat from a Venetian Turkish coat.

Is there any difference?

There are several distinct and fairly consistent differences we can see between the coats portrayed in the renaissance paintings, and the images of coats seen in Ottoman art from around the same period, as well as the extant Ottoman coats we are fortunate enough to have available to study.

The following section will look at each of those differences.

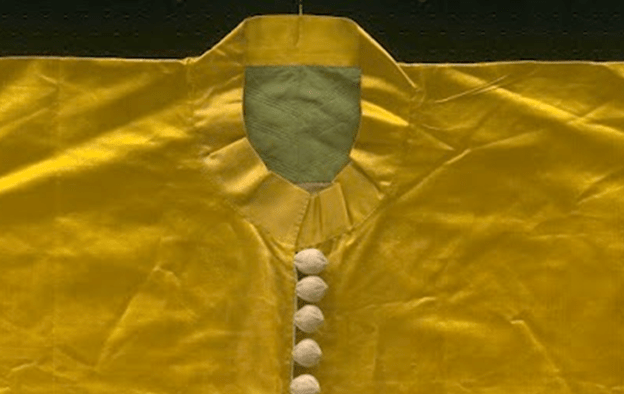

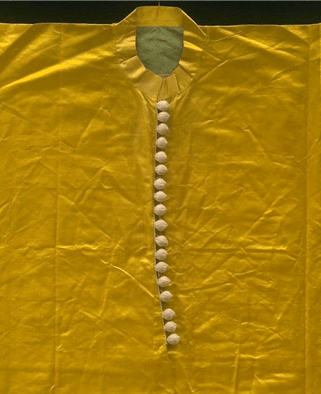

Necklines:

The Venetian coats depicted all have deep V-necks, while the Turkish coats generally have much higher and more rounded necklines. These are sometimes shown worn with the top several buttons left undone.

I have also noticed a fair number of short standing collars on the extant Ottoman examples.

I am not sure if this was a personal style preference, or if it might be specific to coats intended for men vs. women.

I need to investigate this further at some point.

Front Openings:

The Venetian coats have a straight center front opening with no added gores and no overlap. The front appears intended to just meet, and in some cases have an intentional gap.

The Turkish coats have gores added to each side of the center front opening, creating an overlap with no gaping across the upper part of the body and minimal gaping around the lower half of the body when worn.

Buttons/Closures:

Compared to the Turkish coats, the Venetian examples feature minimal closures, typically set some distance apart and occasionally in pairs.

These closures can be made of pearls or beads, or knotted cords, sometimes extending to the hem of the garment and sometimes securing only the upper portion of the garment.

These closures are often a design feature, intended to stand out and be part of the overall embellishments.

On the Turkish examples the closures are typically cloth or knotted buttons, set close together from neckline to waist.

These buttons appear to be made of the same, or at least a coordinating, fabric as the coat, and blend into the garment instead of standing out.

Sleeves:

The Venetian coats all feature short sleeves with most having a distinctive centered point to the opening.

The sleeves feature a variety of embellishments including added trim, beads, and different configurations of cuts or slashes to the body and edges of the sleeves.

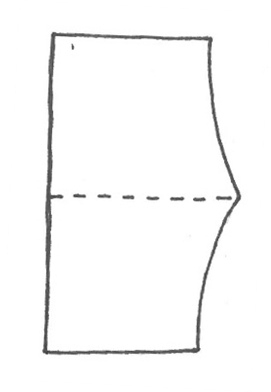

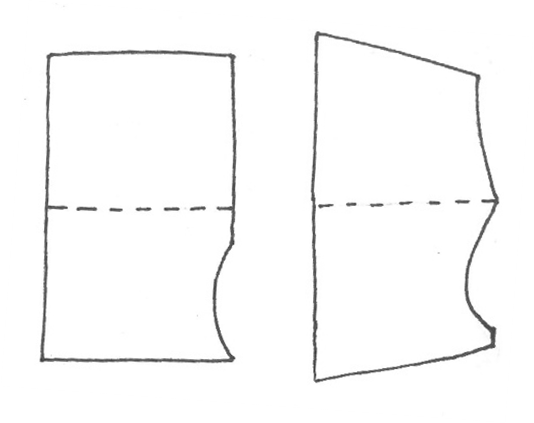

The Turkish sleeve features no added embellishment and has a different but still distinctive shape to the opening in the form of a rounded cut out area at the front edge of the sleeve.

I believe this to be a clever way of avoiding bulk and wrinkles at the bend of the elbow.

Left is a simplified version; Right is based off pattern by Janet Arnold.

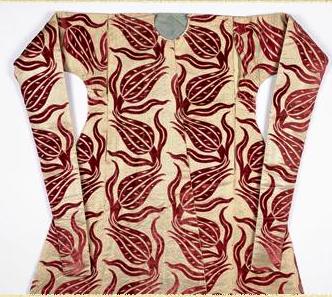

Fabrics and trims:

The Venetian coats appear to be made from a variety fabrics, including solids (possibly cross-woven for an iridescent effect), stripes, and small-scale patterns.

The standout feature of these coats are the trims used to embellish them, often including opulent and heavy trims down the center front of the coats made up of pearls, beads, and gems.

Turkish coats rarely have added embellishment or trims, save for the occasional woven trim across the front of the chest as part of the closures.

The fabrics, however, bring in the wow factor often featuring large scale repeat patterns in bold and contrasting colors. Sometimes the motif is woven into the fabric, but in several instances the motifs are appliqued onto the base fabric of the coat, or block printed on.

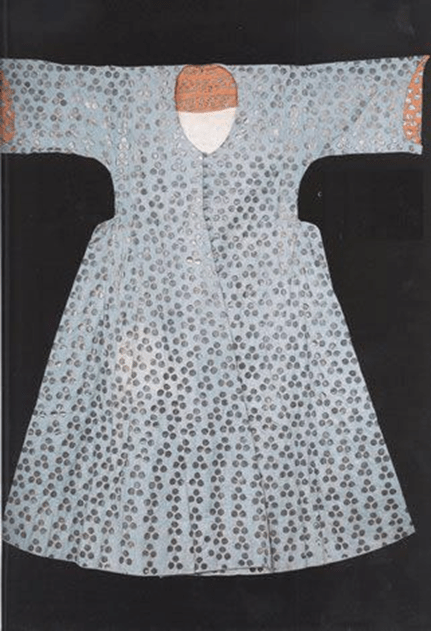

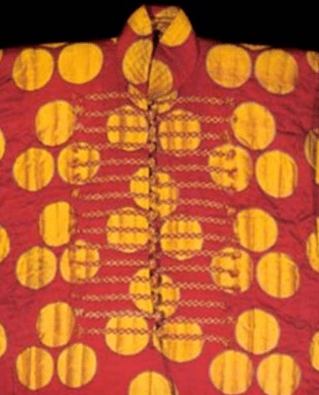

Silk satin with inlaid appliqué design and stamped pattern

Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul, 13/558

“Dazzling in design and conception, this kaftan clearly illustrates Ottoman efforts to transform costumes into visual drama. Instead of relying on woven patterns, relatively simple repeat motifs were “applied” to the satin surface, hence the term appliqué. Although the appliqué technique was less complex than that of brocaded silk, velvet, or cloth of gold and silver, it offered new possibilities in exploiting color, scale, texture, and design with stunning results.” (“Robe (Kaftan) – National Museum of Asian Art”)

Smithsonian national Museum of Asian Art

https://asia.si.edu/explore-art-culture/interactives/style-and-status-imperial-costumes-from-ottoman-turkey/robe-kaftan-13-558/

Examples of boldly patterned Ottoman Kaftans.

So, are Venetian Turkish coats and Turkish Ottoman coats distinct garments?

Yes, they are.

And this led to my decision to also make a Turkish Ottoman coat to fully understand and showcase the differences between the individual garments.

I have the impression that the women of Venice saw the Turkish coats and were like,

“I love that! But let’s make it less modest and add way more bling!”

Or to quote my favorite movie costume blog:

“I don’t care if it’s historically accurate, I just want my tits out.”

Frock Flicks

frockflicks.com

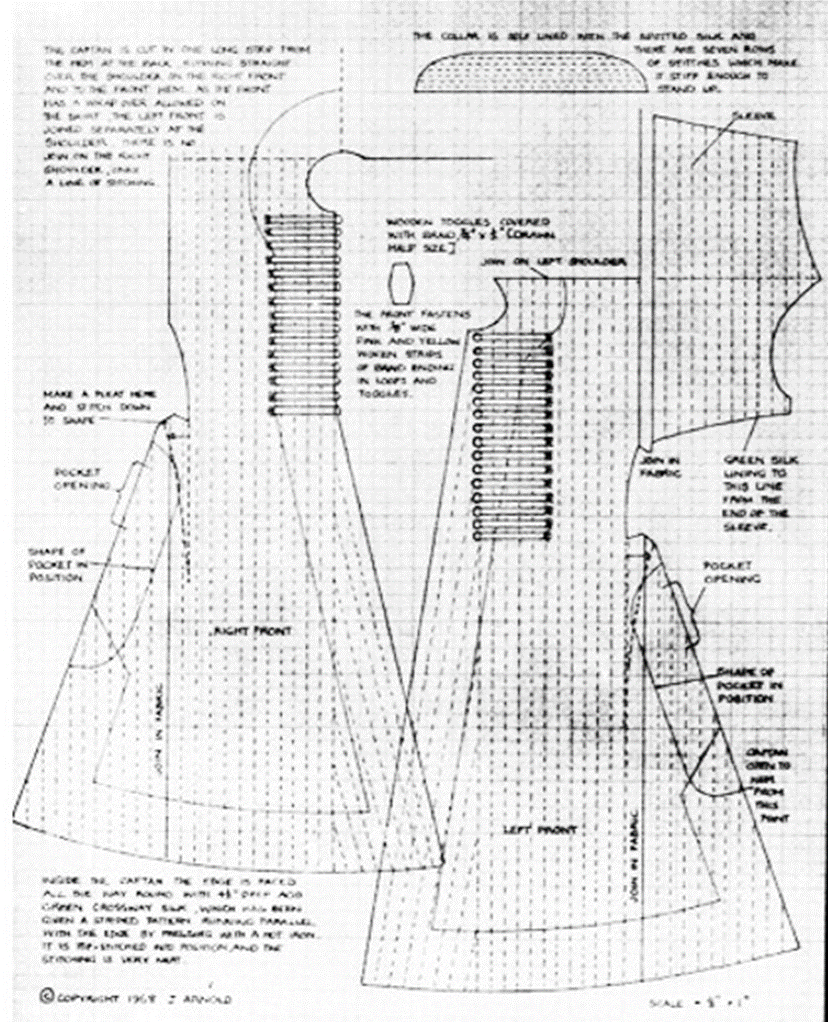

Surprise side-quest!

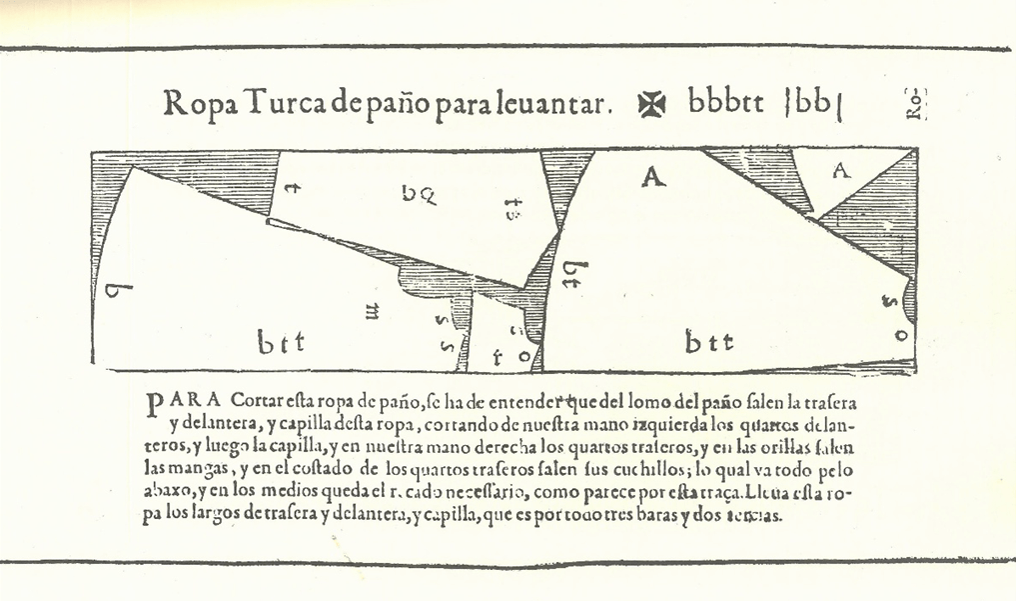

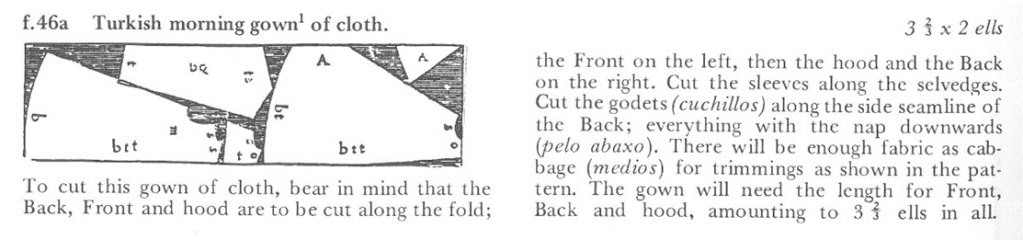

In my research I came across a tantalizing reference to a pattern in a 1580’s tailors manual for a “Ropa Turca de pano para leuantar”, or as best as google translate could give me: a Turkish morning robe.

I was extremely excited at the thought of finding an actual pattern from the period for the exact garment I was working on!

I promptly inter-library loaned a copy of the “Tailor’s Pattern Book, 1589” by Juan de Alcega, and spent several evenings puzzling over the pattern.

It looked simple enough, but I was struggling to wrap my brain around a few of the elements and how they went together.

I had the idea of making a scale model of the garment, hoping that in making it I would figure out what I was missing. I figured doing a scale model would be relatively easy, since this pattern book works off the bara tape method, and my very vague understanding of the bara method is that it is easy to customize size and fit.

So, in a quest to try and fully digest the bara tape method in about an hour and a half, I purchased a digital copy of Mathew Gnagys “The Modern Maker Vol.2: Pattern Manual 1580-1640”.

(Why Volume 2 and not Volume 1 you ask? Because Volume 1 only has guys’ clothes, and if I was going to impulse purchase a book, I was going to get the one with pretty dresses in it too.)

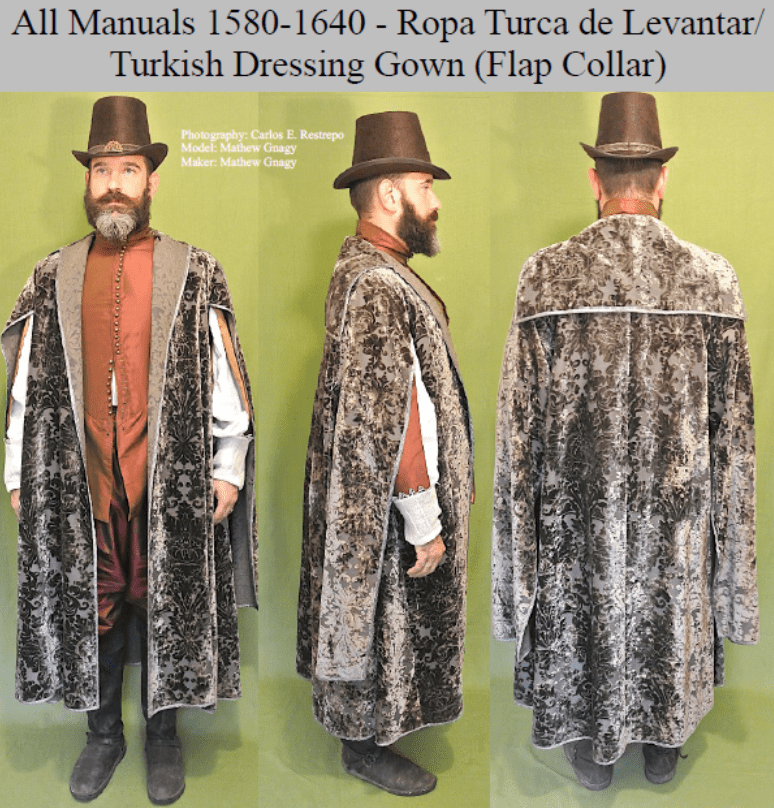

Imaging my glee discovering that this book includes a section on the exact Turkish morning robe pattern I was trying to puzzle out!

With photos of a constructed version!!

No scale model making necessary after all!!!

And then imagine my disappointment realizing that this coat is not really like the coats from the paintings as all.

Bummer.

Still, I do plan to learn the bara tape method.

Eventually.

And I will be making this Spanish Turkish robe at some point, because one can never have too many fabulous coats to swish about in. I mean, just look at those sleeves!

The Countries

Venice and the Ottoman Empire: #FrenemiesForever

- frenemy, noun

- fren·e·my ˈfre-nə-mē

- plural: frenemies

- “informal: a person who is or pretends to be a friend but who is also in some ways an enemy or rival”

- “Frenemy.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/frenemy. Accessed 21 Aug. 2025.

The following is a quote from “Venice and the Ottomans-The Metropolitan Museum of Art”:

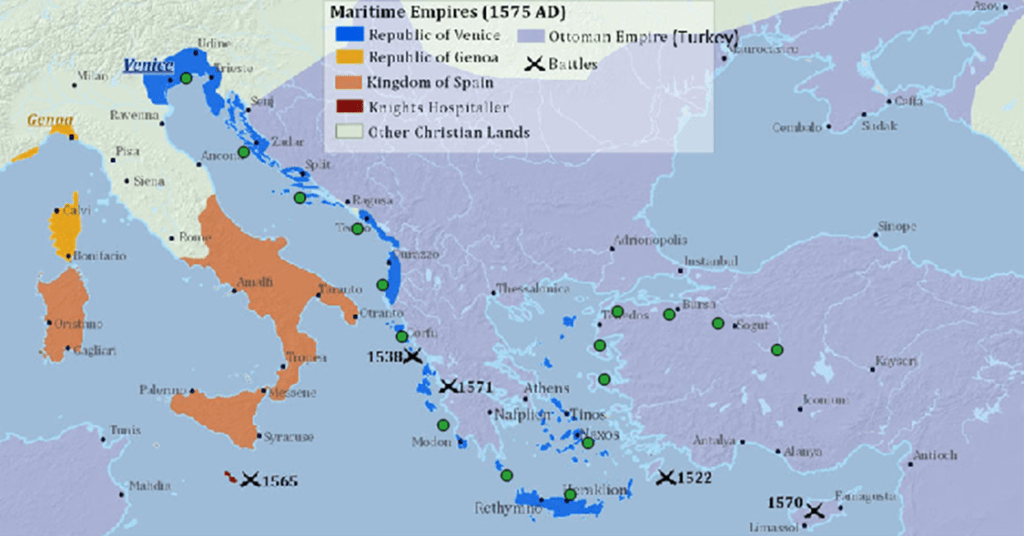

“Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Venetian and Ottoman empires were trading partners—a mutually beneficial relationship providing each with access to key ports and valuable goods. (“Venice and the Ottomans – The Metropolitan Museum of Art”) Though territorial wars intermittently interrupted their relationship, both empires relied on trade for their economic well-being.

As a Venetian ambassador expressed, “being merchants, we cannot live without them.”

“The Ottomans sold wheat, spices, raw silk, cotton, and ash (for glass making) to the Venetians, while Venice provided the ottomans with finished goods such as soap, paper, and textiles. The same ships that transported these everyday goods and raw materials also carried luxury objects such as carpets, inlaid metalwork, illustrated manuscripts, and glass. Wealthy Ottomans and venetians alike collected the exotic goods of their trading partner and the art of their empires came to influence one another”

The Met Museum

The Most Serene Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire had a complex relationship marked by both rivalry and cooperation, especially within the realm of commerce.

And at the heart of their economic ties was the silk trade.

“During the Medieval age, silk production had already spread from China to Persia, India and Syria and to Italy; the latter country becoming the most important producer of silk. The Crusades had helped bring silk production to Western Europe, in particular to many Italian states.”

“Images of Venice: The Silk Trade of Venice“

Venice, a major hub of silk production in Europe, exported fine textiles such as damasks, brocades, and velvets, often interwoven with gold and silver threads.

These goods were prized in Ottoman markets, where fashion trends and courtly tastes created a strong demand for Venetian silks. Despite intermittent wars and political tensions, both countries recognized the mutual benefits of trade.

This enduring trade relationship not only enriched both countries, but also fostered cultural exchange, with Venetian silk influencing Ottoman fashion and vice versa.

Even during changing alliances, and economic challenges, silk remained a thread weaving these two cultures together.

https://www.charlie-allison.com/venice-and-the-islamic-world